On March 21, GOOD Meat, the lab-grown, “cultivated” meat division of Eat Just Inc., announced that it had received an important preliminary approval from the FDA to bring one of its alternative meat products to market in the US. The approval, in the form of a “no questions” letter, means that the FDA has accepted the company’s claim that its first product, cultivated chicken, is safe to eat. The evaluation process involved a detailed submission from GOOD Meat about the safety and production process for the product, including assurances about its nutritional content and purity.

The letter comes two years after GOOD Meat received its first approval, from the government of Singapore, and served its chicken product to the public for the very first time, at upmarket Singapore restaurant called 1880. It has since been sold in a variety of locations in the city-state, from street stalls to the prestigious Huber’s Butchery. At present, GOOD Meat remains the only producer of lab-grown meat in the world not only to have the necessary approvals to sell its products to consumers, but also to have done so. Although Upside Foods secured FDA approval before GOOD Meat, it has yet to feed any paying customers.

GOOD Meat is now working with the US Department of Agriculture to secure the final necessary approvals, before serving its cultivated chicken at a restaurant in Washington DC, with the help of chef José Andrés, who also happens to be a member of the company’s Board of Directors.

“Since Singapore approved GOOD Meat for sale, we knew this moment was next. I am so proud to bring this new way of making meat to my country and to do it with a hero of mine, Chef José Andrés,” said Josh Tetrick, co-founder and CEO of GOOD Meat and Eat Just, in response to the FDA approval.

“The future of our planet depends on how we feed ourselves,” added Andrés. “And we have a responsibility to look beyond the horizon for smarter, sustainable ways to eat. GOOD Meat is doing just that, pushing the boundary on innovative new solutions, and I’m excited for everyone to taste the result.”

Despite the fanfare for this supposed “food of the future,” and the fact that consumers in the US are probably going to be eating it very soon, there remain serious questions to be answered. Not only about the product, but also the man who produced it: Josh Tetrick.

Can eating lab-grown meat – which is essentially a form of deliberately grown cancer – actually give you cancer? How can you convince the public that it won’t, when nobody has ever eaten it before? And is a man with a troubled business history – a history he’s done his best to hide – the right person to do it?

THE CRUELTY-FREE FOOD OF THE FUTURE?

Lab-grown meat, meat that is produced in a bioreactor in a high-tech manufacturing facility rather than on a traditional farm, is widely touted as a “food of the future”, along with so-called “plant-based meats” and new alternative protein sources like insects and algae.

The promise of lab-grown meat is almost too good to be true: all of the benefits of meat – the taste, the texture, and the nutritional profile – without any of the downsides. That means no raising and slaughtering of animals and, even more importantly, claims of a significantly reduced carbon footprint versus traditional agriculture. Agriculture is widely portrayed as one of the principal culprits in the deepening “climate crisis,” with predictions of looming catastrophe if we don’t transform animal farming soon. By “transform”, of course, many simply mean “get rid of altogether”.

Huge amounts of money have already been poured into lab-grown meat, on the promise of an imminent transformation of meat production and consumption. The so-called “Big Three” players – Eat Just, Believer Meat and Upside Foods – have raised $1.2 billion between them in venture funding, and counting.

These new companies have the backing of organizations like the World Economic Forum, which has proposed a “Planetary Health Diet” built around plant-based and alternative protein sources, as well as the UN and governments – including now the US government, and the governments of the UK, France, the Netherlands and Singapore.

Activist celebrities have been at the forefront of this revolution in food production, providing vocal support, as well as financing, for the new technology. In 2021, for instance, Leonardo DiCaprio bought an unspecified stake in two lab-grown meat companies, Mosa Meat and Aleph Farms, after an earlier investment in Beyond Meat, one of the leading producers of so-called “plant-based meat”.

In a press release to accompany his investment in lab-grown meat, DiCaprio said, “One of the most impactful ways to combat the climate crisis is to transform our food system. Mosa Meat and Aleph Farms offer new ways to satisfy the world’s demand for beef, while solving some of the most pressing issues of current industrial beef production.”

With the enormous weight of such individual and institutional backing, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the success of lab-grown meat is all-but-guaranteed. But lab-grown meat faces at least two serious, related, problems that are intrinsic to what it is and the way it is produced. If these problems cannot be resolved, the product may just as easily fail to sell, regardless of how much money has been invested in it.

Manufacturers of lab-grown meat like to say that their product is indistinguishable from real meat. It isn’t a copy, nor replica, nor approximation of real meat: it is real meat. But this isn’t true. In actual fact, lab-grown meat cells differ from typical animal cells in at least one fundamental regard: they will replicate eternally if placed under the right conditions. As a result, they are functionally indistinguishable from cancer. They are cancer. As you might imagine, this brings with it image and safety concerns that are likely to prove very hard to shake.

Cells that replicate eternally are known in the medical business as “immortalized cell lines”. The first immortalized human cell line was produced from cancer cells taken from a woman called Henrietta Lacks in 1951, at Johns Hopkins Hospital, in Baltimore. The sample was taken from Lacks without her informed consent, and her treatment is held up today as a test case of failed medical ethics, alongside other injustices like the Tuskegee experiments. Despite the ethical controversy that still surrounds their use, the HeLa line of cells, as it is known, has been responsible for a number of scientific and medical breakthroughs. Immortalized human cells taken from aborted fetal tissue were used to develop a number of the COVID-19 shots. Cells may already be cancerous, or cancerous growth may be induced in them via the application of radiation or substances such as enzymes like telomerase, or by genetic modification.

Producers of lab-grown meat favor immortal cell lines for much the same reasons scientists do. Since normal cells will only go on dividing so long, constant samples would need to be taken from animals to continue production. As well as increasing costs, this would also give the lie to the claim that lab-grown meats are “cruelty free”, since animals would still need to be raised – and ultimately slaughtered at some point – to produce them. What would be the point?

While using immortalized cell lines may partially solve one problem – the need to justify the product as an (ethical) alternative to traditional meat – it creates an entirely new one, since now producers and consumers must reckon with some of the least desirable associations you could possibly devise for a food product. Whatever safety concerns manufacturers of other alternative products have faced – perhaps most notably Impossible’s novel ingredient “heme” – simply pale in comparison.

Some manufacturers of lab-grown meat, believing the C-word image problem to be intractable, are quietly moving away from using immortalized cell lines and trying different technologies instead. The Big Three, however, are still pushing on with the use of immortalized cell lines and, if a recent Bloomberg Businessweek piece is any indication, they are doing their very best not to acknowledge the endlessly replicating elephant in the room.

But this will hardly do. It’s abundantly clear from polls and market-research data that alternative products like plant-based meats are already viewed negatively, with consumers being deeply skeptical about their taste and health benefits. One amusing survey of Australian men revealed that 70 percent would prefer to lose ten years of their lives than give up meat. A study revealed that the only effective way to get people to choose plant-based options over traditional choices is to shame people with social pressure, and especially messaging about the environmental and ethical cost of not changing their habits. Add the word “cancer” to the mix, and it’s likely that many consumers will have to face down the barrel of a gun before they choose to eat lab-grown meat.

Could consuming these products actually give you cancer? The answer is, simply – we don’t know. Humans haven’t ever made tumors a staple of their diet, so we have zero long-term data about the effects consumption could have. Worries about the safety of lab-grown meat are real enough that the Italian government is now in the process of banning it, much to the dismay of activists and advocates at organizations like the Bill Gates-funded Good Food Institute. The country has also made moves to restrict the addition of insect protein to foods like flour, pasta, and pizza.

Where cancer is a risk, most would be likely to plead for abundant caution, but this is precisely what is not being exercised, except perhaps in Italy. Although we don’t have long-term safety data, we have good reason, prima facie, to believe that eating lab-grown meat could give you cancer.

First, we know the human genome has acquired hundreds of genes “horizontally”, i.e. from other organisms, including bacteria (“vertical” transfer is the “normal” route, from parent to offspring). Although we don’t fully understand the mechanisms by which this has happened in our history, we can be sure, at least, that it has. Second, we know that complete genes pass from food, via our gut, into our blood. Third, we know that horizontal gene transfer, from cancerous to non-cancerous cells, is a central part of the progression of cancers. Cancer cells create bubbles, or exosomes, to transfer genetic material into healthy cells and make them cancerous.

There’s no reason, then, to believe that oncogenes – i.e. cancer-causing genes – present in lab-grown meat couldn’t be assimilated into the genome of an eater. Certainly, any scientist who said this could never happen would be mistaken or lying.

EAT JUST INC.: A “CULT OF DELUSION”?

The formidable difficulties of disrupting an industry, let alone an industry as fundamental and as popular as animal-based agriculture, would be hard enough without factoring in a product that could give consumers cancer. Truly, you’d need an extraordinarily capable leader to do it. But is Josh Tetrick that man? To answer that question, let’s take a look at how Josh Tetrick, and his company, got to where they are today.

The story of the CEO of Eat Just Inc. begins in 2011 with perhaps the closest approximation to a startup fairytale you could imagine.

Two childhood friends – indeed two Joshes, Tetrick and Balk – founded a company.

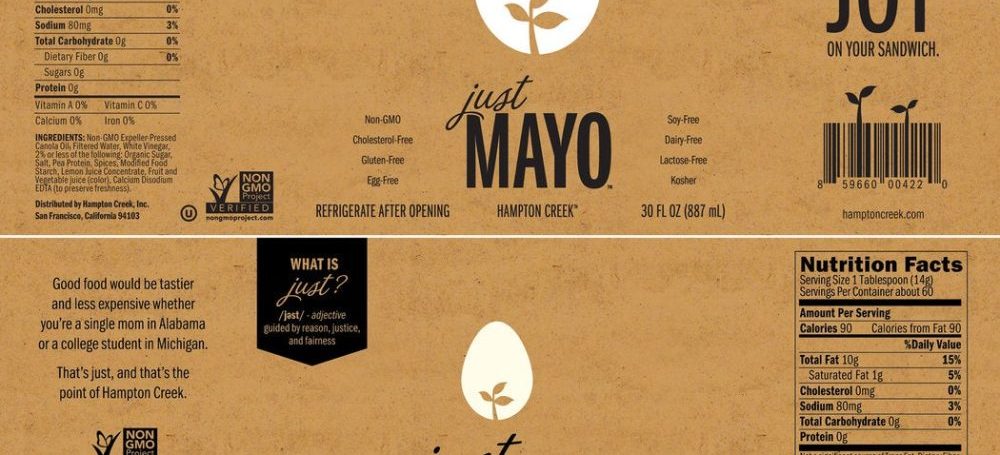

The aim: to revolutionize food by offering ethical alternatives to traditional animal-based products. The initial focus is on replacing eggs in products like mayonnaise and cookie dough. They start out as small as possible, working from Tetrick’s garage in San Francisco. Within two years, which they spend largely on research and development, they manage to secure tens of millions of dollars of venture capital from some of the richest men in the world. This included Bill Gates as well as Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing. In 2014, they bring their first product to the market. It’s a plant-based mayonnaise. And they team up with Whole Foods, as well as with Costco and Safeway. By the end of that year, the company raised almost $130 million in funding.

If the first couple of years for the company were a fairytale, what followed would be anything but dreamlike. Just how bad things would get is best illustrated by just three years later, when the company would be forced to rebrand entirely and even change its name. Because before Eat Just Inc. was Eat Just Inc., it was Hampton Creek.

Mere mention of the name Hampton Creek is enough to elicit an extremely defensive response from anybody associated with Just Inc. When I started mentioning Hampton Creek on Twitter, I found myself almost immediately blocked by the accounts of GOOD Meat and JUST Egg, another brand within the Just Inc. group. Tetrick himself, with whom I had been speaking in a private Twitter groupchat, in the hope of arranging a live debate about the future of food, unceremoniously left, without a word. Hampton Creek is a touchy subject, and it’s not hard to see why.

The problems began in October of 2014, when Hampton Creek was sued by Unilever for false advertising over its plant-based mayonnaise. Although the lawsuit was dropped, Hampton Creek was slapped with a warning from the FDA that it would have to tighten the marketing of its product.

Less than a year later, several former employees came forward as part of a Business Insider exposé entitled, “Sex, lies and eggless mayonnaise: something is rotten at food startup Hampton Creek, former employees say.”

At least six former employees of the company alleged that it was using “shoddy science”, or even ignoring science altogether, to sell its products; making deceptive claims on its sample products; and creating “an uncomfortable and unsafe work environment”. It was even alleged that Tetrick’s dog, which roamed the company’s laboratory, was used to test the shelf life of its products.

“Many Silicon Valley startups exaggerate about how advanced their technology is, the properties of their products, and other metrics. But many former Hampton Creek employees say the company pushed them beyond their ethical comfort levels. One former employee called it a ‘food company masquerading as a tech company.’” Another employee called the business a “cult of delusion”.

The story was met with silence by Tetrick and representatives of Hampton Creek.

In 2016, Bloomberg ran a story claiming that Hampton Creek employees were encouraged to buy their own products, in order to inflate sales figures when the company sought further venture funding. Hampton Creek’s bizarre response was to say that, yes, it did encourage its employees to purchase its products, but only as a form of internal quality control. The Securities and Exchange Commission and Department of Justice launched a formal investigation, and concluded the allegations were not significant.

At this point, Hampton Creek was still able to raise significant interest in the American investor community, achieving a unicorn valuation of $1 billion in August 2016; although the exact amount of funding it had raised was unclear.

The scandals kept coming. In June 2017, Target pulled all of Hampton Creek’s products after allegations of food-safety problems, including salmonella and listeria contamination, at the manufacturing facility. At the same time, a power struggle was also taking place within the company. By July, the entire board had resigned, been fired, or moved to other roles. “Hampton Creek’s expiration date gets closer as board quits en masse”, reported Fortune. The company’s response was that the move was a voluntary one towards a new model of governance based on “advisors” rather than a traditional board.

It was at this particularly troubled time in Hampton Creek’s young life as a company, just six years after it was founded, that the CEO and his “advisors” decided a rebrand would be needed. The company began to transition to focus on the “Just” name, and in 2018 changed the name legally.

The rebrand wasn’t without its own problems, including a lawsuit from Jaden Smith, son of the actor Will Smith, who alleged copyright infringement against his own brand, Just Goods. Just Inc was now failing to raise the money it wanted, at least in the US. The newly minted Just Inc was widely known as a “business with a chequered past”. As a result, the company turned east, to investors in China and the Middle East, to raise the hundreds of millions of dollars it needed for further expansion. This explains why the company was pursuing its first approvals – and its first paying customers – not in the US, but in Singapore.

WHAT NOW?

While the history of Just Inc and Hampton Creek may read like a catalogue of errors, bad judgment calls, and ego-driven style-over-substance marketing, it can also be read as a story of dogged persistence. Persistence that is now paying off.

Tetrick and his company have bounced back from scandal and setback, again and again, and are poised to be the first to serve lab-grown meat to American consumers. Just Inc now has a 30,000 square foot manufacturing facility in Appleton Minnesota – a far cry from the company’s early days in Tetrick’s garage – as well as a manufacturing facility in Singapore, from which it hopes to break into the massive Chinese market in particular. The company recently signed a contract for 10 bioreactors which could be used to produce 30 million pounds of cultured meat in the US a year.

The real question is not whether lab-grown meat is going to be on the menu – that now seems an inevitability – but how much of it people are going to eat and, more importantly, whether it will do them any good.

While the current fortunes of flagship meat-alternative companies like Impossible and Beyond Meat might suggest that these products, and others like them, are destined for the trash-heap of history, reports of their demise are greatly exaggerated. The truth is billions of dollars have been invested in these new products and they have the full moral and institutional backing of most of the scientific, political, and cultural establishments.

One company or product may die – even, eventually, Impossible or Beyond Meat – but hydra-like another three will pop up to replace it. Take a look at a list of new California startups, or the latest round of investments by a venture capitalist like Paul Graham, and you’ll see that the alternative-food ecosystem is becoming more and more crowded by the day, not less. The world’s largest meat-producing corporations, players like JBS and Tyson, are aggressively pushing into new “ownership envelopes”, restructuring their businesses and acquiring salmon-aquaculture and insect farms and vegan pea-protein companies. They’re rebranding themselves too, not as producers of traditional foodstuffs like meat or dairy, but macronutrients, especially protein. Tyson has already trademarked “the Protein Company”.

A fundamental realignment of food production is taking place, and consumer choice, once the reigning value, will now surrender its throne. Advocates and producers of alternative foods are well aware that consumers, given a free choice, would overwhelmingly rather stick with the foods they know and love. Free choice has to go. This is why shame, as well as economic trends, especially inflation and the cost-of-living crisis, and of course the “climate crisis”, are being leveraged more and more to move consumers away from traditional animal products. The idea of “climate rationing” of meat and other foodstuffs is already gaining ground as a response to rising temperatures and carbon emissions, alongside other schemes to limit personal mobility and consumption, like “15-minute cities”.

The danger, for advocates of traditional animal products, isn’t that people will vote with their dollars and start buying lab-grown meat and insects instead of the products they used to eat, but that they will be put in a position where there’s no alternative. If real meat is off the market for good, we may have no choice but to take Josh Tetrick at his word and eat his cultured meat instead.

On the basis of his past performance alone, I’d say that’s a risky proposition indeed.