This article is part of a series focusing on Lens of Liberty, a project of the Vernon K. Krieble Foundation.

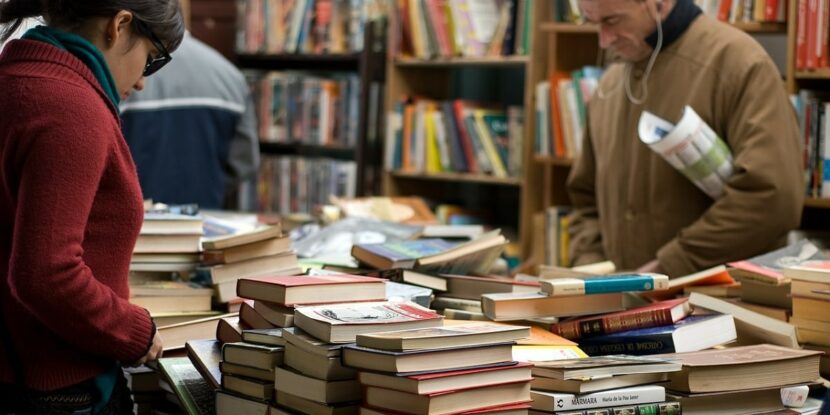

Much to the dismay of many American readers, brick-and-mortar bookstores are quickly becoming a dying breed. But while our first instinct may be to point our fingers at Amazon and other online book-selling websites, the blame must also be placed on federal, state, and local bureaucrats whose needless meddling and regulations accelerate the extinction of small mom-and-pop businesses, including bookstores.

In a Liberty Minute entitled “The Right to Keep and Bear Books,” Helen Krieble shares the story of a bookstore in Los Angeles with a very fitting name:

When Josh Spencer opened his business in Los Angeles, he called it ‘The Last Bookstore’ because so many others have gone out of business in this digital age. But in L.A., the problem is more than just internet competition. That city treats used book stores the same as gun shops.

Owners need a police permit and must hold all books at least 30 days before selling them. Each book must be stamped with a number corresponding to records identifying the book and where it was purchased. And sellers and suppliers must be fingerprinted. That applies to all books, even copies of the Constitution.

Ruthless dictators may hate books, but this is America. People here should look through the lens of liberty and instead of regulating copies of the Constitution, they should read it.

Yes, you read that right. Besides requiring used bookstore owners to obtain a police permit, the city goes further by even requiring they thumbprint every person they receive a book from. Bookstores are also required to comply with an extensive labeling process under which each book must be immediately stamped, printed, or otherwise permanently affixed with a label identifying its “bill of sale” number. This number corresponds to a record kept on permanent file containing, among other things, the date the books were purchased and the name and address of the person that they were purchased from. Once all this data is gathered, a daily report must be filed with the Police Department describing all the books acquired that day. Even though the books must be recorded every day, the city also requires used bookstores to hold books for at least 30 days before selling them.

This bookstore was lucky in that it was eventually exempted from these sweeping regulations when a police officer orally informed the shop owner that he “did not have to comply with the Police Commission’s reporting, thumbprint, and 30-day hold requirements.” However, since these requirements are waived on an unpredictable ad hoc basis, many shop owners are less fortunate.

Michael Bindas, Senior Attorney at the Institute for Justice Washington Chapter, included Spencer’s story in his City Study Series “LA vs. Small Businesses.” Examining the extensive rules and regulations governing every move of the city’s entrepreneurs, Bindas was not at all surprised that Los Angeles is suffering economically:

Given such utterly arbitrary barriers to entrepreneurship, it is no wonder that Los Angeles is facing so much economic woe. And while the very existence of these barriers is bad enough, they are made worse by the fact that they usually serve no purpose other than to burden entrepreneurs, sustain the city’s bureaucracy or protect other businesses from competition.

Such needless rules and regulations are absurd. All city governments, and especially those facing difficult times, ought to take a look through Krieble’s lens of liberty and realize that such ridiculous barriers succeed at doing only one thing — hindering the opening of new businesses, thereby thwarting overall economic progress.